The Race for the Digital Twin: State of Whole-Cell Modeling in 2025

For decades, biology has been a field of “parts lists”—sequencing genes, cataloging proteins, and mapping pathways. But the “Grand Challenge” of the 21st century is different: can we simulate an entire living cell inside a computer? The goal is a Virtual Cell—a digital twin that predicts exactly how a cell will behave under any condition, from drug treatments to genetic engineering.

As we move through 2025, the field has split into two powerful, converging streams: the Mechanistic Modelers, who build cells equation-by-equation from the bottom up, and the AI Architects, who are training massive models to learn the “language” of biology from the top down.

Main Methods

Here is the current state of the field, the key players, and the progress achieved so far.

1. Physics-Based Modeling

The traditional “bottom-up” approach: simulating the actual physics and chemistry of the cell.

Zan Luthey-Schulten Lab (University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign)

The Frontiers of Spatiotemporal Reality

While many whole-cell models assume a “well-mixed” environment (treating the cell as a homogeneous bag of chemicals), the Luthey-Schulten group integrates spatiotemporal heterogeneity in 4D (3D space + time). They utilize a sophisticated hybrid workflow that combines Lattice Microbes (for stochastic reaction-diffusion of proteins/RNA) with LAMMPS (for Brownian dynamics of the chromosome) and ODEs (for metabolism).

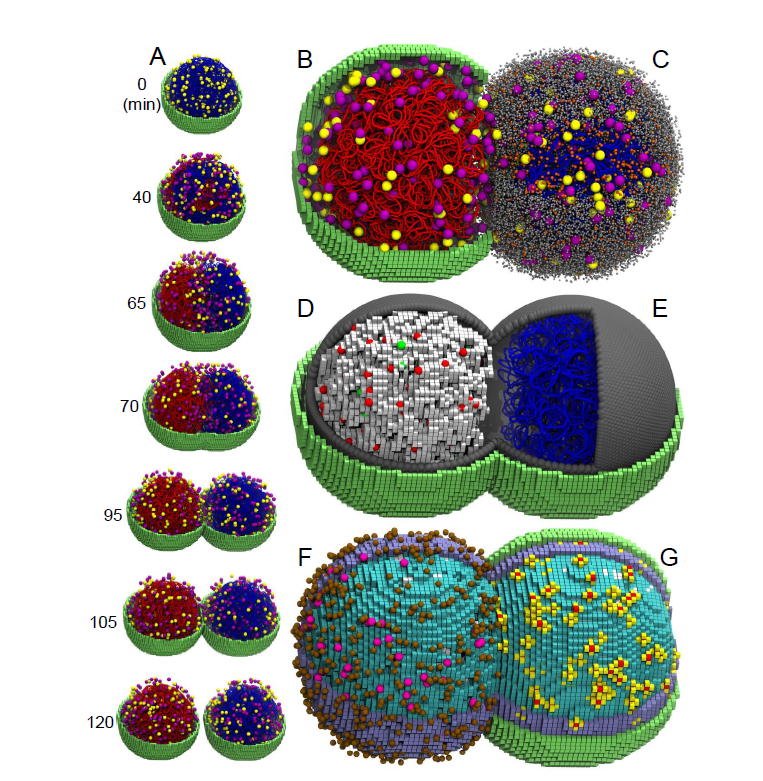

Current Progress: The lab has achieved the first-ever 4D whole-cell simulation of a complete cell cycle for the minimal cell, JCVI-syn3A. Unlike previous efforts that simulated short windows of time, this new model simulates the entire ~100-minute lifecycle, incorporating all genetic information processes, metabolic networks, ribosome biogenesis, and cell division.

Recent Achievement: In 2025, the group successfully simulated the growth and division of JCVI-syn3A in 4D, revealing that every replicate cell is unique due to the stochastic nature of chemical reactions. The model successfully captured the “train-track” replication of the chromosome and its segregation to daughter cells using Brownian dynamics. Crucially, the simulations recovered key experimental measurements—including the exact 105-minute doubling time, protein distributions, and the origin-to-terminus (ori:ter) ratio of the genome—validating that a “digital twin” can now predict complex cellular phenotypes from first principles.

Key Reference:

Thornburg et al. (2025) “Bringing the Genetically Minimal Cell to Life on a Computer in 4D.” bioRxiv. Thornburg et al. (2022) “Fundamental behaviors emerge from simulations of a living minimal cell.” Cell.

Markus Covert Lab (Stanford University)

The Pioneers of Colony-Level Simulation

Markus Covert’s group established the field’s foundation in 2012 with the first complete whole-cell model of Mycoplasma genitalium. They are the leaders in hybrid multi-algorithmic modeling, a technique that partitions the cell into distinct modules (e.g., FBA for metabolism, stochastic solvers for gene expression) and mathematically integrates them to simulate a single cell’s lifecycle.

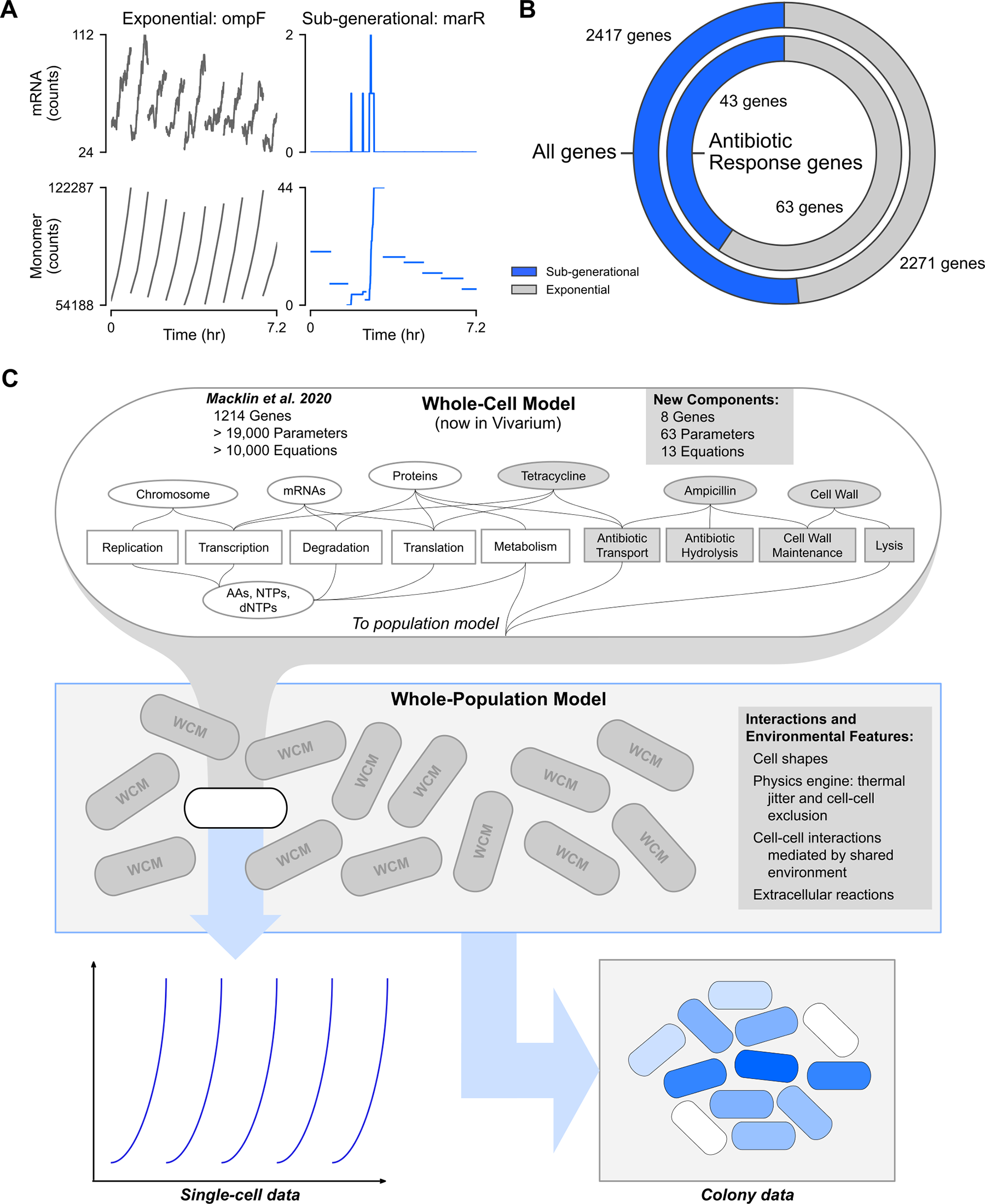

Current Progress: The lab has pivoted to Escherichia coli, a significantly more complex organism. Their E. coli model accounts for the functions of over 43% of all characterized genes. Recently, they have expanded this work to the “whole-colony” scale using the Vivarium software platform, allowing them to embed thousands of individual whole-cell models into a shared spatial environment to study emergent population behaviors like antibiotic heteroresistance.

Recent Achievement: In 2024, the group published a study in Cell Systems using the E. coli model to determine the evolutionary benefits of operon structures. The simulations revealed two distinct modes of utility: for low-expression genes, operons significantly increase the probability of co-expression (ensuring functionally dependent proteins are present simultaneously), while for high-expression genes, operons stabilize the stoichiometry of protein subunits to prevent wasteful overproduction.

Key References:

Sun et al. (2024) “Cross-evaluation of E. coli’s operon structures via a whole-cell model suggests alternative cellular benefits for low- versus high-expressing operons.” Cell Systems.

Skalnik et al. (2023) “Whole-cell modeling of E. coli colonies enables quantification of single-cell heterogeneity in antibiotic responses.” PLOS Computational Biology.

Jonathan Karr Lab (Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai)

The Infrastructure of Trust

You cannot build a whole-cell model if you cannot trust its parts. Jonathan Karr, first author of the original 2012 whole-cell model, has shifted focus to the critical infrastructure required to verify and reproduce these massive systems.

Current Progress: Karr is leading a field-wide “quality control” initiative. In 2025, his team completed a massive verification of the BioModels repository, ensuring that over 1,000 published models actually produce consistent results across different simulators. Without this verification, combining sub-models into a whole cell is impossible.

Recent Achievement: The lab released RBAtools (2024) and standardized SED-ML Level 1 Version 5 (2025). These tools allow researchers to model how a cell allocates limited internal resources (like ribosomes) and tell a computer exactly how to run a simulation, transforming “virtual cells” from one-off scripts into reproducible software artifacts.

Key Reference: Smith et al. (2025) “Verification and reproducible curation of the BioModels repository.” PLOS Computational Biology.

2. The AI Paradigm Shift (Data-Driven Modeling)

The new “top-down” approach: using Transformer models (like ChatGPT) to predict cell behavior without knowing the underlying equations.

The “AI Virtual Cell” (CZI Biohub / Arc Institute)

The Silicon Valley Moonshot

Backed by the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative (CZI) and NVIDIA, this project aims to leapfrog physics by training massive “Foundation Models” on biological data. In October 2025, this ambition scaled up significantly with the announcement of the Virtual Cells Platform (VCP), a centralized open-source hub powered by NVIDIA’s GPU infrastructure to host models, datasets, and benchmarks.

Current Progress: The group is moving beyond single-cell transcriptomics to “multi-modal” foundation models. The new Virtual Cells Platform now hosts diverse models including CodonFM (an RNA foundation model) and MONAI (for biomedical imaging), allowing researchers to fine-tune these massive models for specific tasks without needing their own supercomputers.

Recent Achievement: In 2025, the Arc Institute released two landmark models:

-

Evo 2 (Feb 2025): A 40-billion parameter genomic foundation model trained on 9.3 trillion DNA bases. Unlike previous models, Evo 2 has a 1-million-token context window, allowing it to generate entire mitochondrial and bacterial genomes from scratch and predict the effects of mutations across the whole tree of life.

-

State (June 2025): A dedicated “Virtual Cell” model trained on 170 million cells. It specializes in predicting how a cell’s state shifts after perturbation (e.g., drug treatment), outperforming previous linear methods by 50% in accuracy.

Challenge Results: The inaugural Virtual Cell Challenge, concluded in December 2025, tasked the global AI community with predicting the effects of genetic perturbations in human stem cells. The top honors went to:

- BioMap Research (Team BM_xTVC): 1st Place ($100k prize)

- XLearning Lab: 2nd Place ($50k prize)

- Team Outlier: 3rd Place ($25k prize)

Key Insight: They frame cell biology as a language problem. If you read enough DNA/RNA “text,” you can write the future of the cell.

3. The Software Ecosystem

The tools that make it possible.

Virtual Cell (VCell) Team (UConn Health)

PI: Leslie Loew

While “AI Virtual Cell” is a project name, VCell is the actual software platform used by thousands of biologists since the late 90s.

Current Progress: VCell remains the gold standard for reaction-diffusion and spatial modeling. The latest release (VCell 7.6, July 2024) and recent updates have solidified its integration with rule-based modeling (using BioNetGen), allowing users to simulate complex signaling networks with combinatorial complexity. The team has also introduced “Virtual FRAP,” a dedicated tool for analyzing fluorescence recovery after photobleaching experiments, directly bridging microscopy data with simulation.

Moving Boundaries & Mesoscale: VCell’s capabilities now extend to moving boundary problems—simulating cells that change shape or divide while chemistry occurs inside them. In late 2024, the group advanced mesoscale simulations, using particle-based methods (SpringSaLaD) to parameterize cell-scale continuum models, effectively linking molecular crowding to whole-cell behavior.

Reference: https://vcell.org/

Vivarium (Agmon & Covert)

PI: Eran Agmon (University of Connecticut)

As models get complex, you need “glue” to stick them together. Vivarium is a Python-based interface that allows a metabolic model written in one language to talk to a signaling model written in another. It is the operating system for the mechanistic whole-cell models of the future.

Current Progress: Vivarium is evolving into a formal “Compositional Systems Biology” framework. In 2024, Agmon introduced “Process Bigraphs,” a new mathematical structure for Vivarium that standardizes how biological processes (like transcription or metabolism) nest and connect, similar to how circuits are designed.

Recent Application: Beyond bacteria, Vivarium is now driving multi-scale cancer research. In a 2024 Cell Systems paper, the team used Vivarium to integrate multiplexed imaging with agent-based models, successfully identifying how tumor phenotypes shift during T-cell therapy.

Reference: Agmon E, Spangler RK, Skalnik CJ, Poole W, Peirce SM, Morrison JH, Covert MW. Vivarium: an interface and engine for integrative multiscale modeling in computational biology. Bioinformatics. 2022 Mar 28;38(7):1972-1979. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btac049. PMID: 35134830; PMCID: PMC8963310.

Summary: The Convergence

We are witnessing a convergence. The Mechanistic groups (Covert/Luthey-Schulten) provide the ground truth and physical constraints, while the AI groups (CZI/Arc) provide the scalability to handle human complexity. The “Holy Grail” will likely be a hybrid: an AI model that learns from data but is constrained by the laws of physics provided by mechanistic simulations.

The Virtual Cell is no longer science fiction; it is an engineering problem.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: